More on 19th Century Efforts To Eject City Island Businesses from Land Beneath Waters Surrounding the Island

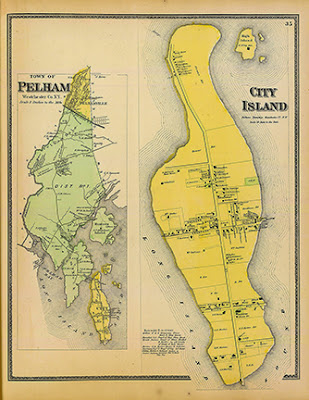

In about 1889, Elizabeth D. De Lancey brought the suit against Henry Piepgras, owner of one of the largest shipyards on City Island. See Tue., Dec. 08, 2015: Heinrich Carl Christian "Henry" Piepgras and His Shipyard in the Town of Pelham on City Island. In it she alleged that in 1763, the English Crown granted to Benjamin Palmer, owner of City Island, an interest in all land under the waters surrounding City Island and extending 400 feet into Long Island Sound from the high water mark on the island. Palmer needed the underwater lands to build docks, wharves, and more as part of his plan to create a port to rival that of New York City in New York Harbor. Under the grant, Palmer was required to pay an annual rent of "five shillings sterling" at the Custom House in New York City, to the tax collector or receiver general. Palmer never paid the annual rent.

Following the Revolutionary War, the State of New York took over the English Crown's interest in such land and tax receipts. In 1836, the State of New York commenced proceedings for forfeiture of the underwater lands surrounding City Island for non-payment of the annual rent. Upon the successful close of the proceeding, New York City offered the land for sale at auction. A man named Teunis Van Vechten bought the property with a bid of $8.10, but transferred his successful bid to Des Brosses Hunter who acquired the land. Des Brosses Hunter was the father of the plaintiffs in the later lawsuit, Elizabeth Hunter De Lancey and John Hunter. Des Brosses Hunter received a comptroller's deed for the land under the waters surrounding City Island.

After the death of Des Brosses Hunter, a three-quarters interest in the underwater lands devolved to his daughter Elizabeth De Lancey and a one-quarter interest devolved to his son, John Hunter. Over the years, however, City Island had evolved into a maritime village with wharves, docks, shipyards, and marine railways (all of which extended into the waters surrounding City Island). In the late 1880s, Elizabeth De Lancey decided it was time to proceed against all those shipyards, businesses, and others who had built structures out into the waters of Long Island Sound encroaching on the underwater lands owned by her and her brother. She apparently chose the large shipyard of Henry Piepgras as her test case and, in 1889, filed suit against him seeking ejectment. Soon her brother was joined into the lawsuit as well.

Henry Piepgras and his attorneys fought the suit valiantly. Nevertheless, the New York Supreme Court (trial court) ruled in De Lancey's favor. Piepgras and his attorneys appealed to the Appellate Division which also ruled in De Lancey's favor. Piepgras and his attorneys appealed to the New York Court of Appeals which ruled, once again, in De Lancey's favor in 1893.

The decisions were devastating for Piepgras and shocked the entire City Island community. Finally De Lancey had the sheriff block Piepgras from using his marine railways, docks, and portions of other structures that extended into the water, virtually shutting down his shipyard.

Henry Piepgras was not finished with the matter. He filed a lawsuit against one of the plaintiffs' lawyers, Walter D. Edmunds, and plaintiff John Hunter alleging that Edmunds prepared an improperly-worded judgment that was executed by the trial court at the end of the De Lancey's lawsuit and then had the sheriff execute that judgment in a fashion that unnecessarily shut down the Piepgras Shipyard and cost Piepgras $15,000. In October, 1893, a Special Term of the Superior Court of New York City rejected the claims asserted by Piepgras, giving De Lancey and her brother the final upper hand.

City Islanders in the Town of Pelham now would have to come to the negotiating table, hat in hand, and deal with De Lancey and her brother if they wished to maintain their docks, wharves, shipyards, marine railways and the like.

Below is the text of a brief news article and of two important decisions in the string of judicial decisions involving the matter. Each is followed by a citation and, in one instance, a link to its source. In addition, I have written before about the lawsuit to eject Peipgras. See Mon., Nov. 27, 2006: The 19th Century Ejectment of Henry Piepgras from Land Beneath the Waters Surrounding City Island.

"IT IS ALL MRS. DE LANCY'S [sic]

-----

Court of Appeals Sustains Her Title to Land Under Water Around City Island.

Mrs. Eliza D. De Lancy [sic] won in the Court of Appeals last week her long-pending suit for the belt of land beneath the water which surrounds City Island. This belt is 400 feet wide and contains 145 acres. It is said to be worth more than $100,000. Mrs. De Lancy's father, Elias D. Hunter, bought it from the State of New York for $8.10. The land was granted by the Crown of England in 1763 to some residents of City Island for the purpose of wharves and shipyards. They were to pay a quit rent of eight shillings per annum to pay the Crown.

After the Revolution the State of New York succeeded to the right to receive this quit rent. The rent was in default from the very first, and in pursuance of an act of the Assembly, passed in 1819, the State sold the land at public auction in 1826 [sic], to Teunis Van Vechten, who before the delivery of a deed, transferred the bid of $8.10 to Elias D. Hunter, the father of Mrs. De Lancy. The Hunter or De Lancy title was recognized in Westchester county for a great many years.

A few years ago residents on City Island began to ignore the De Lancy title, and the owners of land on the island proceeded to acquire riparian title from the Land Commissioner's office. The land under water became valuable, as shipyards sprung [sic] up on the island. Mrs. De Lancy tried to get the City Islanders to recognize her title and buy her out. She failed, and four years ago she brought suit to establish her title to all the property. Justice Maynard rendered the decision of the Court of Appeals which places her in possession of all this valuable property. The style of the suit was DeLancy vs. Piepgrass [sic]. Lawyer Walter D. Edmonds, Mrs. De Lancy's counsel, says that he brought this test case against Henry Piepgras because he was the richest man on the island. He owns a large shipyard there. In this case the Court of Appeals decided for the first time that the title to lands under water around islands in the Sound did not pass by the old Pell grant which established the manor of Pelham."

Source: IT IS ALL MRS. DE LANCY'S -- Court of Appeals Sustains Her Title to Land Under Water Around City Island, The Sun [NY, NY], Apr. 23, 1893, Part 3, p. 5, col. 2.

De Lancey v. Piepgras, 138 N.Y. 26 (N.Y. 1893).

"MAYNARD, J.

The plaintiff and the defendant John Hunter have recovered in ejectment from the appellant the possession of a strip of land under water adjacent to Minnefords, or City island, in Long Island sound, extending into the sound four hundred feet at right angles to ordinary high-water mark. The premises are a part of a tract of land under water of the same width, comprising about one hundred and forty-five acres, completely surrounding the island, and described in letters patent issued to Benjamin Palmer, May 27, 1763, in the name of the Crown of Great Britain, by Robert Monckton, captain-general and governor-in-chief of the province of New York. The respondents' title and right of recovery depend, in the first instance, upon the operation and effect of this grant, the habendum clause of which provides that the lands shall be held by Palmer in free and common socage, as of the manor of East Greenwich, in the county of Kent, yielding, rendering and paying therefor yearly, and every year forever, to the king of Great Britain, at his custom house in New York city, to his collector or receiver-general, there for the time being on Lady Day, the annual rent of five shillings sterling, in lieu and stead of all other rents, services, dues, duties and demands whatsoever, for the premises granted, and every part and parcel thereof; and also upon the validity of a comptroller's deed of the same, executed in 1836 to the devisor of the respondents under proceedings had by the authority of the state for a forfeiture of the patent for non-payment of the quit-rents.

Many objections are urged against this recovery by the appellant's counsel, with great learning and ability, which demand the most serious attention, and which we will consider in the order in which they arise in the development of the respondents' title. First. It is insisted that the royal grant to Palmer is overreached by another patent from the Crown, issued in 1666 to Thomas Pell and confirmed in 1687 to his nephew John Pell, creating the manor of Pelham, comprising a large territory upon the mainland opposite Minneford island, and including the island, and by virtue of which it is claimed that the title to the land under water about the island became vested in the patentee. It must be admitted that if the patent to Pell was an ordinary conveyance, even from the sovereign power, it would not extend beyond high-water mark, and that lands below that point would not pass by the deed, unless actually included in the expressed metes and bounds of the grant. ( Rogers v. Jones, 1 Wend. 237; Gould v. James, 6 Cowen, 369; Cheney v. Guptill, 2 Hannay, N.B. 379; Trustees of Brookhaven v. Strong, 60 N.Y. 56; Roe v. Strong, 107 id. 358.) The descriptive part of the instrument is limited to the mainland and the islands in the sound opposite. It is a conveyance of a tract upon the mainland bounded on the south by Long Island sound, with all the islands in the sound not previously granted or disposed of, "lying before the tract upon the main land," which extends inland eight English miles, with the same breadth in the rear "as it is along by the sound." The burden of proof is upon those who claim below high-water mark, and it has been held that a private grant, which included an arm of the sea with all islands, ponds, ways, waters, water courses, havens and ports, was insufficient at common law to convey the soil between high and low-water mark. (Gould on Wat. 69; East Haven v. Hemingway, 7 Conn. 186, 200; Middletown v. Sage, 8 id. 221; Jackson v. Porter, 1 Paine C.C. 457; Com. v. Roxbury, 9 Gray, 457, 478, 493.)

It is true that the patent to Pell was also a grant of a manorial franchise, with administrative and judicial powers, such as the establishment of a court leet and a court baron, and the learned counsel, whose brief is specially devoted to this point, takes the ground that the conveyance must be regarded as a public grant, which includes within the scope of its operation all the lands under water, to which the jurisdiction of the lord of the manor extended. In some measure the right of local self-government was given, and it was declared in the deed that the lands and premises conveyed should forever thereafter, 'in all cases, things and matters be deemed, reputed, taken and held as an absolute intyre, infranchised towneshipp, mannor and place of itselfe in this government,' and that it should hold and enjoy the same privileges and immunities as any town within the colony. This bestowal of political rights and powers did not, however, enlarge the property rights of the patentee. They were franchises of a public character to be held and exercised by him as the representative of the Crown or of the colonial government. It may be admitted that civil and criminal processes issued by him might be lawfully executed upon the adjacent waters, but the proprietorship of the soil under the water would not follow as an incident of this power. The right of jurisdiction and the right of property must not be confounded. The former could be restricted or even abrogated by the authority which granted it and became subject to the control of the state, upon the adoption of the first Constitution; the latter was a matter of private ownership, of which the proprietor could not be divested, except by his own act or by due process of law.

The case of Martin v. Waddell (16 Peters, 369), is cited at great length by counsel, but we think it is destructive of the appellant's claim in this respect. It involved the construction of the grant made by Charles 2nd to the Duke of York, by means of which authority was given to establish a colonial government over a vast extent of territory bordering upon the sea coast. It was there held that the patentee became vested with the title to the lands under water, not, however, in his private right, but as the representative of the Crown, and as a part of the royal prerogatives, or jura regalia, which it was presumed he would administer for the public good. While these colonial charters were in the nature of grants, and were conferred by the king as proprietor, yet as they respectively created governments, they were not construed as his other grants were, that is, as excluding the adjacent waters, but as including them, and thus the government of the respective colonies had ample authority to alter the established law with regard to their tide waters, or to grant an exclusive property therein, at their discretion. (Angell on Tid. Wat. 37, 38.) The different rule of construction to be applied in the two classes of cases is defined with great clearness and emphasis by Ch. J. TANEY.

The grant is to be applied with strictness, where it is the gift of some prerogative right to be held by the citizen as a franchise, and which becomes private property in his hands. It will not be presumed that the sovereign power intended to part with any of its prerogatives, or with any portion of the public domain, unless clear and express words are used to denote the intention. But colonial charters were designed to be the instruments upon which the institutions of a great political community were to be founded; and their provisions must be liberally interpreted, whenever necessary to accomplish the purpose of their creation.

There was no departure from these principles of construction in Trustees of Brookhaven v. Strong ( 60 N.Y. 59), and the other cases involving the jurisdiction of the Long Island towns over the adjacent tide waters, to which our attention has been called. In the Brookhaven case, the right of the town to a portion of the waters of the Great South bay, and the lands thereunder, was upheld because they were expressly included within the boundaries of the grant, and their control was a part of the royal prerogatives conferred, and the authority of the town over them had been recognized by both colonial and state legislation.

It must, therefore, be held, we think, that the Crown did not part with the title to these lands when the manor of Pelham was created, and that it became vested in Palmer by the grant to him in 1763.

Second. The patent to Palmer was liable to forfeiture, for a failure to pay the quit-rent reserved; and the several acts of the legislature authorizing the sale of the lands because the rent was in arrear, were sufficient to terminate the estate of the patentee, and reinvest the sovereign with the original title. Notwithstanding the grant, the king still had the reversion, now called the escheat, and there was the obligation of fealty on the part of the grantee, which if broken, would also cause the estate to revert, and in all such cases, if rent was reserved, it became a rent service, and the estate granted a qualified or conditional fee.

In the feudal economy, rent had a two-fold quality. It was regarded as something issuing out of the land, as a compensation for the possession; and also as an acknowledgment by the tenant to the lord, of his fealty or tenure. A quit-rent was so called because the tenant thereby went quit and free of all other services (1 Woodfall on L. T. 375, 6, 7). In case of a rent service, its payment was a condition subsequent implied in law, and essential to be observed, in order to insure the continuance of the grant. After the enactment of the statute of quia emptores in the 18 of Edward I, no such condition would be implied in a grant in fee, between individuals. Every freeman might then sell his lands at pleasure; the system of subinfeudation was destroyed, and feudal restraints upon alienation abolished. What would have before been regarded as a rent service, because of the implied obligation to render it, would in subsequent grants become a rent charge or a rent seck, and a failure to pay would not of itself work a forfeiture of the estate. But as the king is not bound, unless the statute is made by express terms to include him, the tenure created by royal grants was not affected by this change in the law; and every conveyance, emanating from the Crown, reserving rent, still created a rent service and involved the possibility of forfeiture. For a breach of the condition, the king might by inquisition have the estate of the tenant declared at an end, resume possession, and his original seizin would be restored unaffected by the previous demise. The patent to Palmer was, therefore, burdened with this condition, and the interest of the Crown in the lands granted, with the right to the rents reserved, and to re-enter for non-payment became vested at the Revolution, in the people of the state, who it is declared in the Constitutions of 1777 and 1821, have succeeded to all the rents, prerogatives, privileges, forfeitures, debts, dues, duties and services, formerly belonging to the parent government, with respect to any real property within the jurisdiction of the state. Thereafter the people in their sovereign capacity, were the lord paramount; and had authority to terminate the grant to Palmer, for failure to discharge the rent service imposed by it.

The state was not restricted in the choice of remedies, if it sought to avail itself of the grantee's delinquency, so long as the course pursued clearly evinced an intention to reassert title, and resume possession. The mode in which it should be done was subject to the legislative will. It might be the result of an authorized judicial investigation, or by taking possession directly under the authority of the government, without any preliminary proceeding. A legislative act directing the appropriation of the land, or that it be offered for sale or settlement, or any other legislative assertion of ownership, is the equivalent of an inquest of office at common law, finding the fact of forfeiture, and adjudging the restoration of the estate on that ground. This was substantially the rule laid down by NELSON, J., in U.S. v. Repentigny (5 Wall. 267), in the case of a grant by the French crown, where the Federal government had re-entered for condition broken, and reiterated in many subsequent cases. ( Schulenberg v. Harriman, 21 Wall. 44; Van Wyck v. Knevals, 106 U.S. 368; St. Louis, etc., R. Co. v. McGee, 115 id. 469; Bybee v. Oregon Cal. R.R. Co., 139 id. 675.)

By chapter 222 of the Laws of 1819, the comptroller was directed, as soon thereafter as might be practical, to advertise and sell all lands chargeable with quit-rents, upon which the rent might be in arrear, on some day to be named by him not less than twelve months from the date of notice, and, if the land sold should remain unredeemed for two years after the sale, to convey the same to the purchaser by deed, under his hand and seal of office, and witnessed by the deputy comptroller. By various supplemental statutes, the sale was postponed until the first Tuesday in March, 1826, when, by chapter 251 of the Laws of 1825, the comptroller was directed to commence the sale, having previously given notice thereof in at least one public newspaper in the county where the lands were situated, and to sell only for such sums as the owners were required by law to pay as commutation for the rents reserved, which by the act of 1824 (Chap. 225) was fixed at two dollars and fifty cents for each shilling, if paid before May 3, 1825, and with an addition of ten per cent if paid thereafter. Pursuant to this authority, the lands described in the patent to Palmer were sold by the comptroller in 1826, and bid off by Teunis Van Vechten, and a certificate of sale issued to him by the comptroller. Van Vechten assigned his bid and certificate to Elias D. Hunter, the respondent's devisor, to whom the comptroller executed a deed in due form on April 5, 1836. The legislative purpose, as indicated in these enactments, to enforce a forfeiture and resume the possession and control of the estate granted to Palmer, is, we think, too clear and certain to admit of question. This purpose was effectually accomplished by the proceedings of the comptroller taken in conformity therewith. We do not hold that a mere assertion by the legislature of a forfeiture for condition broken will conclude the patentee, or those in privity of estate with him, from showing that he was not in default, and that no rent was in fact due, and that, therefore, there could have been no forfeiture legally enforceable, but such a claim or defense can only be available to those deriving title under the patent, and cannot inure to the benefit of strangers to the title. It will be presumed that the sovereign authority did not act without knowledge or proof of the existence of a cause of forfeiture, and, until overthrown, this presumption will be sufficient to support their action.

Third. The comptroller's deed to Hunter established, prima facie, the existence of the jurisdictional facts authorizing a sale of the lands. It recited a compliance with all of the provisions of the law upon the subject, and being regular and valid upon its face, extrinsic evidence was not required in order to render it admissible as the act of the state. A deed by a public officer in behalf of a state is the deed of the state, although the officer is the nominal party. (Gerard on Titles [3d ed.], p. 18; Sheets v. Selden, 2 Wall. 177.) The rule is firmly established that the issuing of a patent by the officers of a state, who have authority to issue it, upon compliance with certain conditions, is always presumptive evidence of itself that the previous proceedings have been regular, and that all the prescribed preliminary steps have been taken; and the recitals in it are evidence against one who claims under the original owner by a subsequent conveyance, or does not pretend to claim under him at all, and the grant cannot be impeached collaterally in a court of law upon the trial of an ejectment. (3 Wn. on R.P. [5th ed.] p. 205; People v. Mauran, 5 Den. 389; People v. Livingston, 8 Barb. 277; Steiner v. Coxe, 4 Penn. St. 28; Hill v. Miller, 36 Mo. 182; U.S. v. Arredondo, 6 Pet. 691; Bagnell v. Broderick, 13 id. 436; E.G. Blakeslee Mfg. Co. v. Blakeslee, 129 N.Y. 155, 160.)

It was said by the Federal Supreme Court in the Arredondo case, which was a Spanish grant (p. 727), that "the public acts of public officers, purporting to be executed in an official capacity, and by public authority, shall not be presumed to be an usurped but a legitimate authority, previously given or subsequently ratified. If it was not a legal presumption, that public and responsible officers, claiming and exercising the right of disposing of the public domain, did it by the order and consent of the government in whose name the acts were done, the confusion and uncertainty of titles and possessions would be infinite in this country."

The rule which governs where the title rests upon a tax sale has no application. In such cases the state proceeds in a summary way to seize and appropriate the property of the citizen in invitum, and the sale and conveyance are but steps in the proceeding, which must be shown to have been duly instituted and regularly prosecuted, or the attempted confiscation will fail, unless there is some statute which makes the deed presumptive or conclusive evidence of regularity. In the present case the state was engaged in the sale of its own lands. It was not restricted in the selection of the mode of procedure. The requirements which it imposed were either for its own protection, or an act of grace to the patentee, to afford him an opportunity to redeem from the forfeiture, which the state could, at its option, make absolute. This distinction has been repeatedly pointed out. In Boardman v. Reed (6 Pet. 342), it was said by McLEAN, J.: "That when an individual claims land under a tax sale, he must show that the substantial requisites of the law have been observed; but this is never necessary when the claim rests on a patent from the commonwealth." In the People v. Mauran (supra), which like the case at bar was ejectment on a grant of lands under water, McKISSOCK, J., said: "The principles governing here have no analogy to the rules applicable to the cases to which we were referred on the argument, such as purchases under sales for taxes and the like."

Fourth. The 22d section of the act of 1819 provided that if, at the time of the conveyance, the lands were in the actual possession and occupancy of any person, the purchaser shall serve upon the occupant a written notice of the sale and conveyance, stating the amount of the consideration, and that unless paid, with fifty per cent added, into the state treasury for the benefit of the purchaser within six months from the service of the notice, the conveyance will become absolute, and the occupant and all others interested in the lands be forever thereafter barred of all right or title to the same; and that it should be necessary for the purchaser, in order to complete his title, to show by due proof that such notice had been given, and by the certificate of the comptroller, that payment had not been made as required in the notice.

It is insisted that these premises were actually occupied in 1836, when the deed to Elias D. Hunter was executed, and that in the absence of proof that the required notice was given the plaintiff's title is fatally defective. The evidence in regard to occupancy is substantially undisputed, and hence it becomes a question of law whether it was sufficient to bring the case within the provisions of the statute requiring notice. The testimony of the principal witness for the appellant, who was but nine years of age in 1836, was to the effect that there were two piers, one on the southwest, and the other on the west end of the island, both running down to below low-water mark, built of stone, one about one hundred feet in length running out to a big rock, and about fifteen feet wide, and the other extending fifty or sixty feet out, and from six to eight feet wide. The father of the witness owned the upland on that part of the island, but he did not build the docks or keep them in repair, and the witness states that "They were quite old, ruinous, broken-down stone piles," and that the larger one was evidently built for the purpose of reaching the big rock, so that the people could walk off to the rock and fish there. Another witness for the appellant states, that these stone piers, or jetties as he calls them, were not built by his father, who was the occupant of the upland, and he did not know who built them, or what they were built for; that one of them at least, which was not double, was used as the line fence between adjoining properties, and to keep the cattle from escaping. Other witnesses describe the jetties as water fences primarily designed to restrain the cattle, but, also, used to aid in the landing of boats, and for convenient fishing. These structures do not seem to have been claimed or used exclusively by any individual proprietor, but to have been open to public use. It is quite plain that in view of these conceded facts, there was no actual individual occupancy of the tract of land under water, or of any material portion of it, at the time of the delivery of the comptroller's deed, and that the deed then became completely operative as a grant by the state, without further proceedings on the part of the grantee. ( Smith v. Sanger, 4 N.Y. 577; Miller v. L.I.R. R. Co., 71 id. 385; Roberts v. Baumgarten, 110 id. 385; Roe v. Strong, 107 id. 350; McFarlane v. Kerr, 10 Bosw. 249; Drake v. Curtis, 1 Cush. 411.) In McFarlane v. Kerr, the owner of the upland had continued his boundary fences to low-water mark, to prevent cattle passing around them, and had built a bulkhead and filled in with earth a small portion of the land between high and low-water mark, and had cut sedge thereon, and it was held that this was not such an occupation of the land, as would support a defense of adverse possession. Yet an adverse holding may be upheld in certain cases where there is only a constructive possession of part of the premises, but the statute under consideration requires an actual occupation, in order to impose upon the purchaser the obligation of serving notice upon the occupant.

Smith v. Sanger was a case of a tax sale, where the law in this respect was substantially the same as in the act of 1819, and where the rule of construction is more strict, and it was held that the clearing, fencing and cultivating for the purposes of husbandry of two and one-half square rods, was not such an actual occupation of a lot of two hundred and fifty acres, as required the service of the notice.

Here it is shown by the record that these stone jetties comprised but a few square rods in area out of a tract of one hundred and forty-five acres, and were not claimed or used as private property, and we think it would be a subversion of the purpose of the statute, and a disregard of its letter, as well as its intent, to hold that the land was actually occupied by any person in 1836.

Fifth. The appellant failed to establish the defense of adverse possession. Upon this branch of the case the evidence is not conflicting, nor is it of such a character that different conclusions of fact can be legitimately drawn from it. The appellant's grantor Carll, first went into possession about 1861, of a small portion of the upland bordering upon the shore a distance of one hundred feet, which was used for a ship yard, and had two structures in connection with it called marine railways, each ten or twelve feet wide, extending into the water about two hundred feet, partly above and partly below high-water mark, and capable of hauling up a vessel of one hundred and fifty tons. In 1863, Carll procured through the commissioners of the land office a patent for two and 35/100 acres of land under water, upon which the marine railway had been erected, and in 1865 built a wharf thirty by one hundred feet, at the foot of a street. No other structures were erected more than twenty years before this action was commenced, and those subsequently added need not be considered. Whether they were kept up or used continuously for twenty years does not clearly appear. The appellant testified that when he purchased in 1886, they had all rotted down and been washed away, and the existing improvements were all made by him. In any view it is evident that there was no permanent appropriation of the soil by Carll. The structures were of a temporary character, and designed simply to afford a means of access between the upland and the navigable waters of the sound, and a title in fee will never be implied from user, where an easement only will secure the privilege enjoyed. ( Roe v. Strong, 107 N.Y. 350.)

The statute (Code, § 368) provides that in an action of ejectment, the person who establishes a legal title to the premises, is presumed to have been possessed thereof, within the time required by law, and the occupation of another is deemed to have been under, and in subordination to the legal title, and the burden is thus thrown upon the defendant to prove an actual, adverse and exclusive enjoyment of the property in fee, during the prescribed period.

From the nature of the property, it is difficult to show such a possession of lands under water as is required to support the presumption of a grant, and we fail to find any case where anything short of a permanent and exclusive occupation of the soil has been regarded as sufficient. (Buswell on Lim. Ad. Poss. § 244; McFarlane v. Kerr, supra.)

The use which the appellant's grantor made of this property, for any continuous period of twenty years, is not shown to have been of such a kind as to necessarily require the implication of a grant in fee, to render it lawful, and it is, therefore, not available as a defense, when the owner of the legal title seeks to recover the fee.

Sixth. While the respondents have successfully maintained their title to the fee of the land under water, of which the appellant claims to be the owner, we think the judgment must be in one respect modified. What the state conveyed to Hunter was the property which the Crown granted to Palmer in 1763. That conveyance contained an important proviso to the effect that it should not extend or be construed to extend at any time thereafter, to prohibit or in any wise deprive, prejudice, exclude or hinder any person from any right, liberty or privilege, which he might lawfully have enjoyed if the grant had not been made, in bringing to and anchoring any ship, boat or vessel on the premises granted, or fishing on the same, nor from any other right, liberty or privilege he might have lawfully enjoyed, except upon such parts of the premises as shall at such time or times be covered with wharfs or other buildings erected thereon by the grantee, his heirs or assigns, and reserving to the sovereign, and to all other persons whatsoever at all times thereafter, all such powers, liberties, rights and privileges in every part of the premises not covered with wharfs and buildings, as fully as if the grant had not been made. While the fee was conveyed, yet there was reserved to the public and to the upland owners the right to use the premises for the purposes of fishing, navigation, anchorage and access to and from the island until wharfs and buildings had been erected thereon, and to so use all parts of the premises at any time, not occupied by such structures.

The property rights granted to Palmer were similar in terms to the grants of land under water by the commissioners of the land office, and contained similar reservations, which secure to the people the same measure of enjoyment of the premises conveyed as they were entitled to before the conveyance, until the land has been actually appropriated and applied to the purposes of commerce, or for the beneficial use of the owner, by the erection of docks and other structures thereon. The deed to Hunter is expressly limited to the lands granted to Palmer and did not vest in him any rights which the Crown had reserved and which passed to the people as the successors of the royal power, and of which they did not become possessed by means of the forfeiture of the grant.

The judgment should, therefore, be modified by inserting therein the proviso and reservation contained in the patent to Palmer, and as thus modified affirmed, without costs to either party in this court.

All concur.

Judgment accordingly."

Piepgras v. Edmunds, et al., 5 Misc. Rep. 314 (Super. Ct. of N.Y. City, Oct. 1893).

"PIEPGRAS V. EDMUNDS et al.

(Superior Court of New York City, Special Term. October, 1893.)

IRREGULAR EXECUTION. -- LIABILITY FOR ENFORCEMENT.

An action will not lie for acts done by virtue of an execution which is merely erroneous, and not void, where such execution has not been set aside, but has only been amended nunc pro tunc.

Action by Henry Piepgras against Walter D. Edmunds and John Hunter, Jr. Defendants demur to the complaint. Sustained.

George A. Black, for plaintiff.

T. C. Byrnes, for defendant Edmunds.

John Hunter, Jr., in pro. per.

GILDERSLEEVE, J. The cause of action set forth in the complaint, briefly stated, is as follows: One Elizabeth D. De Lancey, by her attorney, the defendant Edmunds, brought suit in ejectment to recover possession of three-fourths part from Piepgras, the plaintiff herein, of certain lands, below high-water mark, at City Island, impleading one John Hunter, the owner of the remaining one-fourth part of said premises, whose attorney was the defendant herein, John Hunter, Jr., and who, in his answer, demanded judgment for the delivery to him of the possession of the said one-fourth part. The said Piepgras, in his answer in said action, 'admitted that he was seised and in possession, as owner, of said premises, but denied that he unlawfully withheld possession.' The action was tried in the supreme court, Westchester county, and judgment was given for De Lancey and Hunter, respectively, for the recovery of the immediate possession of said premises from said Piepgras, and for execution therefor. Piepgras appealed from both of these judgments to the general term, (17 N. Y. Supp. 681) where they were both affirmed. On appeal to the court of appeals, (33 N. E. Rep. 822) the judgment was modified by inserting therein 'the proviso and reservations contained in the patent of Palmer, and, as so modified, affirmed.' This Palmer patent, as appears from the complaint, granted certain easements, which, by the judgment of the court of appeals, were not taken from said Piepgras. The complaint also sets forth a certain judgment, entered, on the remittitur of the court of appeals, in the supreme court, by De Lancey and Hunter, and a certain execution issued on said judgment by the defendants herein, as attorneys for De Lancey and Hunter. The complaint further alleges that plaintiff was the owner of the upland adjacent to the premises under water, and used the same as a shipyard, and had erected thereon a large and valuable building, plant, and equipment for shipbuilding, and used the same in connection with a dock and several marine railways, all built by plaintiff or his grantors, and extending from the plaintiff's upland to the channel and navigable waters of Long Island sound over the said land under water, which dock and marine railways were essential to the use and enjoyment of said shipyard, and to plaintiff in his business, and were lawfully there, from all of which marine railways and dock, plaintiff was excluded by the sheriff, by virtue of the execution issued as aforesaid, and by virtue of the delivery thereof to the said De Lancey and Hunter by said sheriff, and plaintiff was thereby prevented from carrying on his said business of shipbuilding, and put to great loss, etc. The complaint also alleges knowledge of all these facts by defendants, and that plaintiff had not been deprived of these rights and uses by the judgment of the court of appeals, but was unlawfully deprived of them through the improper wording of the execution issued by the defendants herein upon the improperly worded judgment of the supreme court, entered on the remittitur of the court of appeals. The plaintiff applied to the court to modify the judgment of the supreme court, entered on the remittitur of the court of appeals, by making it conform more closely with the decision of the court of appeals, which motion was granted, and at the same time the execution was modified, nunc pro tunc, to make it conform to the modified judgment. And the complaint alleges that, by reason of all these aforesaid facts, occasioned by the wrongful acts of defendants, plaintiff has been put to great loss, expense, trouble, etc.; and, finally, the complaint demands judgment for the sum of $15,000 and costs. The judgment of the supreme court, entered on the remittitur of the court of appeals, the execution issued thereon, and the judgment as afterwards modified by the court at special term, on plaintiff's motion, are all set forth in the complaint, in full.

The execution does not sufficiently conform to the judgment upon which it was issued, inasmuch as it does not contain a recital of the limitations of the easements set forth in the judgment, but directs the delivery of the possession of the premises, after reciting, among other things, that the court of appeals had “modified” the judgment of the general term. However, it was not a void process. It was sufficiently in conformity with the judgment upon which it was issued to prevent its being void. The judgment itself was a judgment of the supreme court, duly signed by Mr. Justice Dykman, and duly entered. It was not a void judgment, and the defendants were protected for all acts done under and in conformity with it, inasmuch as it has never been vacated, but only modified, and is still, so far as the complaint shows, in force. The execution was not a void process, but simply insufficient, erroneous, or irregular. If an attorney causes a void or irregular or erroneous process to be issued in an action, which occasions loss or injury to a party against whom it is enforced, he is liable for the damage thereby occasioned. In the case of void process, the liability attaches when the wrong is committed, and no preliminary proceeding is necessary to vacate or set it aside, as a condition to the maintenance of an action. Process, however, that a court has general jurisdiction to award, as in the case at bar, but which is irregular or erroneous, must be regularly vacated or annulled by an order of the court before an action can be maintained for damages occasioned by its enforcement. Day v. Beach, 87 N. Y. 56. In such cases, the process is considered the act of the party, and not that of the court, and he is therefore made liable for the consequences of his act. Fischer v. Langbein, 103 N. Y. 89, 8 N. E. Rep. 251. In the case at bar, the process was not vacated, but simply amended, nunc pro tunc, to more nearly conform to the judgment of the court of appeals and to the judgment of the supreme court as amended, upon which it was issued. The execution was erroneous, but not void, and it has not been vacated, but is still in force. It therefore protects the defendants for acts done under it. If the sheriff exceeded his instructions under the execution, he, and not the defendants, is liable. The law may be stated as follows: First. That a void writ or process furnishes no justification to a party, and he is liable to an action for what has been done under it at any time, and it is not necessary that it should be set aside before bringing the action. Second. If the writ is irregular or erroneous, only, and not absolutely void, no action lies until it has been set aside; but, when set aside, it ceases to be a protection for acts done under it while in force. Third. If the process was regularly issued, in a case where the court had jurisdiction, the party may justify what has been done under it after it has been set aside for error in the judgment or proceeding. Day V. Bach, 87 N. Y. 61. In this case, as we have said, the process was erroneous, but not void; and it has never been set aside, but is still in force, as amended nunc pro tunc. I am therefore of opinion that the defendants are protected for the acts done under it, and that the complaint is demurrable. The question whether the process was void may be said to be res adjudicata, inasmuch as the supreme court, at special term, as appears from the complaint, has denied plaintiff’s motion to vacate and set aside the execution for irregularity or erroneousness, has held that it was not a void process, but has amended it nunc pro tunc, as of the time of issuing, to make it conform more expressly to the decision of the court of appeals, and to the judgment, as amended, of the supreme court, upon which it was issued. For the reasons above stated, the demurrer must be sustained, With costs."

Archive of the Historic Pelham Web Site.

Home Page of the Historic Pelham Blog.

Order a Copy of "Thomas Pell and the Legend of the Pell Treaty Oak."

Labels: 1889, 1893, City Island, De Brosses Hunter, Elizabeth DeLancey, Henry Piepgras, John Hunter Junior, Piepgras's Shipyard, Real Estate