Mysterious Rock Construction on Two Trees Island Off the Shores of Pelham

Home Page of the Historic Pelham Blog.

Order a Copy of "Thomas Pell and the Legend of the Pell Treaty Oak."

Two Trees Island was made famous, in effect, by local historian Theodore L. ("Ted") Kazimiroff in a pair of books he published entitled: The Last Algonquin (1982) and If These Trees Could Only Talk (2014). In these books Kazimiroff told the story of Joe Two Trees and his ancestors, Native Americans who once lived in the region of Hunter's Island and roamed the area from the Harlem River to today's Pelham Bay Park and beyond.

In The Last Algonquin, Ted Kazimiroff tells the story of how his father (Dr. Theodore Kazimiroff, former Bronx Historian) was befriended as a young Boy Scout in the early 1920s by an elderly Algonquin who continued to live a simple Native American life while essentially hiding in a vine-covered campsite in the Hunter's Island region of today's Pelham Bay Park. Joe Two Trees, according to the tale, was born in the area more than eighty years before and, in his final months, befriended the young boy and taught him much about Native American ways. Then, as Joe Two Trees neared death in his Native American shelter in the early 1920s, he asked the young boy to listen to his life story and to keep his deeds alive by retelling that story as a way to keep his spirit alive.

When the young boy grew into a man and had his own son (whom he named Theodore L. "Ted" Kazimiroff), he told his young son the story of Joe Two Trees and stories of the ancestors of Joe Two Trees. Ted Kazimiroff later decided to help keep the spirit of Joe Two Trees alive by writing his two books (which I recommend highly as both informative and entertaining reading of interest to those wanting to learn more about the histories of the Town of Pelham, Pelham Bay Park, Hunter's Island, and the Northeast Bronx).

Joe Two Trees was so-named by his mother, Small Doe. She named him after a tiny island off the shores of Pelham with two trees on it at the time. Two Trees Island stood only a few feet north of East Twin Island, once one of a pair of islands known as "the Twins" (West Twin Island and East Twin Island). The Twins, in turn, were a pair of islands immediately east of Hunter's Island. Eventually a small stone causeway was built to connect Hunter's Island to West Twin Island.

During the 1930s, Robert Moses led a project that used landfill to create Orchard Beach and the Orchard Beach Parking Lot which attached Hunter's Island to the mainland. Then, in 1947, an expansion of Orchard Beach joined the Twins to the mainland as well.

Even today it is possible to get to Two Trees Island at low tide simply by walking across to it from East Twin Island via a mudflat that connects the two. One author recently wrote:

"[Y]ou can continue to the northern end of Twin Island and cross over at low tide to Two Trees Island. This charming small island is great for exploring with children. (It is, however, common to find a man or two sunning themselves on rocks in extremely skimpy bathing suits.) Litter can sometimes be a problem, but don't let that stop you from combing the area for arrowheads left by Native Americans and artifacts from early European settlers, which are still occasionally found. The mudflat between Twin and Two Trees Island is also a great spot for finding fiddler crabs and tasty glasswort (a sea-side herb) and beautiful sea lavender in spring and summer."

Source: Seitz, Sharon & Miller, Stuart, The Other Islands of New York City: A History and Guide, p. 135 (3rd Edition - Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press, 2011)

Immediately below is a satellite image showing the area today and indicating the location of Two Trees Island.

The detail below from a map published in 1905 shows the area that includes Hunter's Island, the Twins, Two Trees Island, and other rock outcroppings and islands in the area before Hunter's Island, the Twins, and Two Trees Island were attached to the mainland.

Immediately below is a photograph of Two Trees Island taken several years ago, followed by attribution.

Immediately below is an image of a 19th century painting by Frederick Rondel believed to depict a portion of Two Trees Island with David's Island in the distance behind the sailboat.

Two Trees Island is located adjacent to (and some sources state within) the "Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary" located north of Orchard Beach. See Day, Leslie, Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City, p. 31 (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007) (In Association with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation).

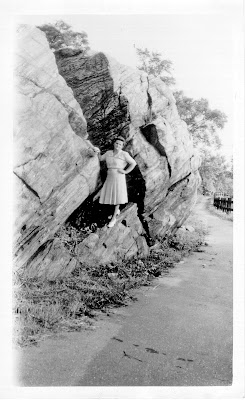

A most intriguing and unusual feature may be found on Two Trees Island. There is a rocky campsite where a rock outcropping likely has been used as a shelter. Ted Kazimiroff has identified this site as the very campsite used by Joe Two Trees before his death in the early 1920s. See Kazimiroff, Theodore L., If These Trees Could Only Talk -- An Anecdotal History of New York City's Pelham Bay Park, p. ii (Outskirts Press, Inc., Copyright 2014 by Theodore L. Kazimiroff). Ted Kazimiroff includes a photograph on page ii of his book showing himself standing in front of the shelter with the following caption: "Ted Kazimiroff, author, in the old campsite. This is where many generations of immigrants to America both Indian and Europeans sought shelter from the elements over thousands of years."

Who built the shelter marked by the flat rocks laid along a sheltering rock outcropping on Two Trees Island? The short answer seems to be: no one knows. Even if Joe Two Trees used the location as a campsite, it does not, of course, mean that the flat rocks laid along the outcropping were his or that they even were laid before (or after) he used the site. Indeed, it is possible to wander the entire areas of Two Trees Island, West Twin Island, and East Twin Island and see rock stairs and even the remnants of sheltered locations such as this one that were built by campers, members of local summer colonies, members of the so-called "Twin Island Cabana Club," and many others who frequented this area throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

It is, for example, well known that members of what once was known as the "Twin Island Cabana Club" built a dozen or more "rock shelters" fashioned by stacking heavy stones to create a shelter from wind and inclement weather on the Twin Islands and, in this case perhaps, on Two Trees Island as well. Similar rock shelters, stone fireplaces, and the like were built on Hunter's Island as well and were used regularly at least from the 1920s through the 1970s. In fact, in a written survey regarding Hunter's Island and its resources prepared in 1974, the author noted the existence of such rock shelters, saying:

"Hunter's Island doesn't have sand covered bathing beaches and access is by foot. However, there is a group of visitors, that because of their unique style and use of the Island, who must enter into this discussion of the area. They are a close knit group of friends and acquaintances, predominantly of Russian and German origin, who visit the place practically every day throughout the entire year. These visits have taken place for the past fifty years. Individually they make their way to the park and meet at certain established places, where they will spend the day enjoying each other's company and cooking their communal meals. They have built stone fire places, picnic tables and shelters for protection against inclement weather. The interior of Hunter's Island is almost completely free of litter since these people, voluntarily, take the responsibility for the cleaning and maintenance of the area. The boardwalk that extends to one of the knolls described before, was built entirely by these groups. They have a tie with Hunter's Island, one built on time and respect."

Source: Geraci, Robert, Hunter's Island Existing Resources and Potential Uses Preliminary Survey, p. 6 (mss; June 1974) (thanks to Jorge Santiago of the East Bronx History Forum for bringing this reference to my attention).

In short, we may never know who constructed the sheltered area on Two Trees Island depicted above. Yet, the name of the island, the existence of the sheltered area, and the two wonderful books by Ted Kazimiroff have kept the spirit of Joe Two Trees alive -- and that seems far more important.

Labels: 1924, Dr. Theodore Kazimiroff, Hunter's Island, Joe Two Trees, Native Americans, Stone Shelters, Theodore L. Kazimiroff, Twin Islands, Two Trees, Two Trees Island